When I was in high school in South Georgia, there was a very specific meaning to the word, “saved,” and it was decidedly religious. In the circles I traveled, it was also binary. One either was or was not.

In mid-2025 America, the word feels far less precise, as if parts of our community life together can still be saved, while other areas may be just gone. At least for my lifetime, some things are over. I don’t think of being saved in religious terms now, I think in terms that give this life meaning, setting aside what may come next.

A point here. There’s a difference between what soothes and what saves. My country desperately needs soothing, at least to the extent that we can learn to talk with each other and still keep our cool. In the past decade, our civic imagination has narrowed. We’ve reduced our neighbors to a binary: either “pro-America” by our own definition, or something else, something suspect. Those who pass the test are tolerated. Those who don’t are quietly removed from our attention.

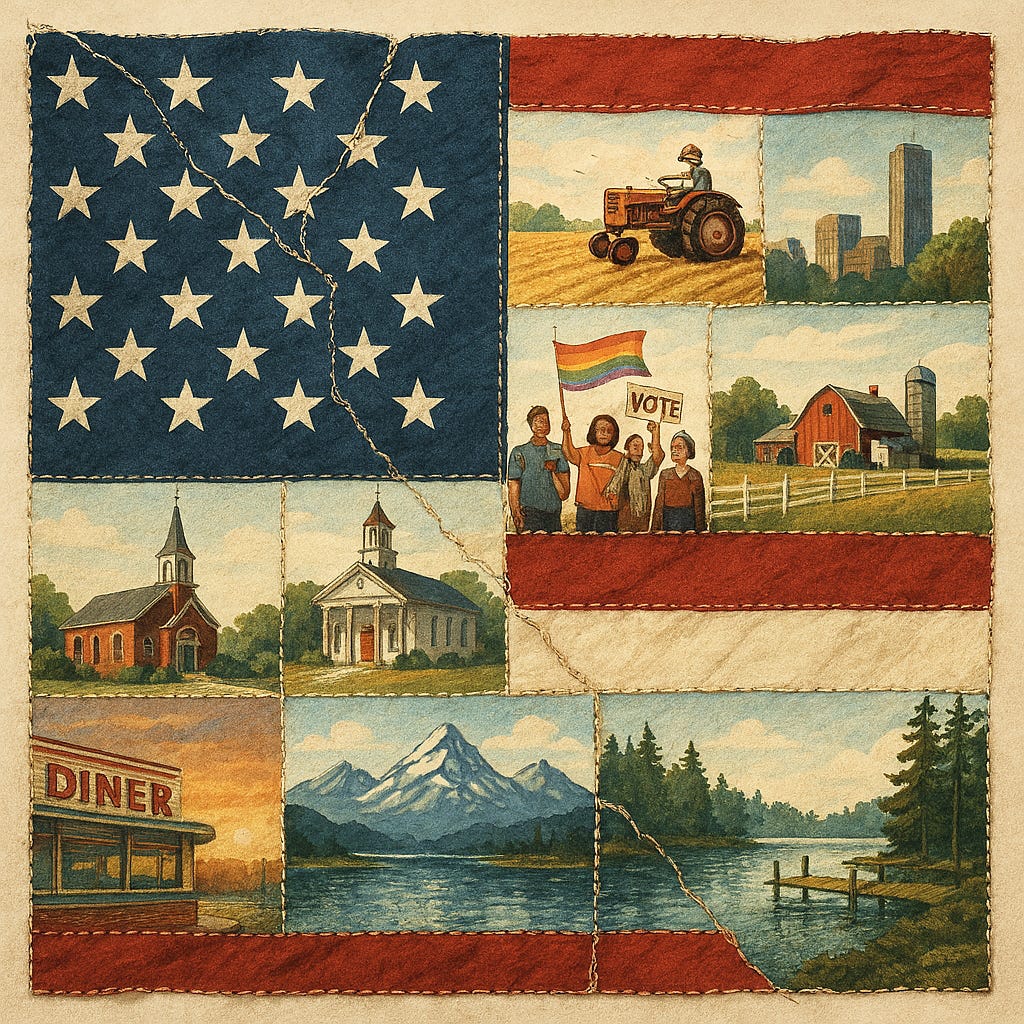

That’s a hell of a fall from the notion of the United States of America. It wasn’t that long ago that families gathered to “show slides” of their visits to the wildly different parts of our country. We shared with pride the visions we gathered of cowboy hats or snow-capped mountains in the summer, or quiet docks on the lake. I could feel the pride of living in a big, diverse country, in how different some states were from back home. How the people there were different but so nice to us.

What Can Be Soothed?

Before I could ask what might be saved, I found myself asking what might be soothed. Not resolved or redeemed, just softened enough to carry. The rapid degradation of America’s quality of life, beyond worst fears, is staggering to many, frightening to the most vulnerable, and self-satisfying to a few. This question of what I need to be soothed, and what soothing is even possible, haunted me deeply, especially early in the year. What I found is that presence, listening, and perspective make a difference.

In recent years, tutoring foreign students in English has become more than a side gig; it’s become a quiet lifeline. These students, mostly intermediate to advanced speakers, come with sharp minds, political curiosity, and a preference for real conversation over textbook drills. What began as language practice has turned into a weekly ritual of global witnessing, an unexpected balm in a time when American civic life feels frayed and fevered.

They ask about crime, racial tension, the cost of housing, or how our healthcare works. Some ask why Americans are often rude tourists but gracious hosts. Sometimes they ask if democracy is still working. I try to answer honestly, without collapsing into despair or defensiveness. Their questions are not accusations so much as invitations. Invitations to see my own country through eyes that are curious, not cynical. Ears that still believe language can build bridges, not just walls. In their listening, I find myself speaking more clearly. In their queries, I remember what it feels like to hope.

I don’t always have answers. Sometimes I offer context, sometimes I admit confusion. But the ritual itself, the logging in, the listening, the mutual curiosity, has become a kind of civic practice. Not grand or performative, just steady. A way of staying tethered to the world without succumbing to America’s current noise. These students remind me that clarity doesn’t always come from certainty. Sometimes it comes from being willing to speak while still unsure.

There’s a kind of emotional pacing in these sessions, too. Despite occupying precious weekend hours, tutoring becomes a rhythm that steadies me when the rest of life feels jagged. I don’t perform optimism, but I do offer presence and perspective. In return, I receive something rare: a space where curiosity isn’t scorned, where a Turkish longing or a Saudi opinion isn’t pathologized. It’s not therapy, and it’s not friendship exactly, but it is a kind of sanctuary. One that reminds me I’m still capable of connection, even in a time of curated reactions and quiet exile here at home.

The phrase ‘news travels fast’ doesn’t quite capture the immediacy anymore. On Saturday morning, just hours after the Alaska summit, a student from Saudi Arabia asked, ‘Why did the United States roll out a red carpet for Putin?’ I’ve learned to stay steady in such discussions, knowing that my own learning often exceeds what I offer.

Perspectives matter. My Turkish students have lived through a political landscape shaped by strongman leadership, democratic backsliding, and deep polarization, experiences that mirror, in unsettling ways, what many Americans are now witnessing. Those insights offer a kind of emotional and civic soothing, reminding me that what feels unprecedented here has echoes elsewhere. They do not paint a rosy picture, but still, to hear someone say, “I remember when we were going through something like you are now. I know how hard it is - how shocking,” lifts me up.

Most evenings, my wife and I watch the MSNBC lineup together. The dialogue that follows is often our richest of the day, an exchange of news tidbits, reflections on something Rachel Maddow just said, or talk of an upcoming protest that feels urgent. To have someone close who shares a civic lens is one of the greatest gifts there is.

In both my engagement in a tutoring session and the digesting of The Last Word with my wife, I find a rhythm that steadies me. Not because the world is less broken, but because I am less alone in facing it. Soothing doesn’t solve the crisis. But it steadies the soul. In this time of fractured civic life and red-state exile, that may be enough to soften the weight. Enough to keep going.

What Can Be Saved?

This summer has been different from the Spring. This summer has felt less like the earthquake of the first 100 days and more like a giant in a red hat prying open our national cracks with a crowbar, gleefully, relentlessly.

At first, my question was, “Can the country ever be reunited?” Now, I’m wondering if any of us wants that.

How many Americans can honestly say that, given our politics and the way we view each other, they would want someone with a different political view to become their new boss or next-door neighbor? I shudder to imagine what that poll result might be. The idea of Americans as one people strains the memory. What was that like?

When I was a child and said I was born in California, people responded with curiosity. Now, to many, California is just a crime-ridden blue state. I wonder if anyone still wonders what Californians are really like.

My MAGA friends tell me that they get dismissed all the time by the coastal elites who don’t know them. In that framing, ‘coastal elite’ simply means anyone who didn’t vote for Trump. I can hear one friend now telling me, “I know you’re not from the coast!” But it doesn’t change the fact that, just as our MAGA neighbors accuse us of tossing Trump voters in one big basket of deplorables, so too many in red hats paint us with a single broad brush.

Perhaps, as a point of personal privilege, we can look at the different kinds of attitudes one encounters. In terms of those who fundamentally disagree with me, it feels as if there are three kinds of people.

Some have high priority issues, perhaps illegal immigration, trans athletes, and national debt. This group seems to genuinely believe that, under Donald Trump, their preferred position on their biggest issues will be best represented. They believe Trump would better represent their priorities than Kamala Harris. I respect this group. They have made conscious decisions about what matters to them and decided how to vote based on what they feel is the best direction. Members of this group are not immune to the implementation of Trump policies and the problems that have come. Some are beginning to question the role of ICE, or to reconsider what the Big Bill will do to the debt.

Group two is most certainly the biggest group. Here, voters support the general direction as defined by Donald Trump during both the 2024 campaign and during his previous 8 years as a public figure and former President. The people here find that the direction of the country is more comfortable for them under Trump than under Biden or his successor. This is harder to accept, but I understand that not everyone has the time or makes the time to go deeper into policy. They go with their gut. That’s not unreasonable. These people may not see the footage of women dragged from their cars, but they hear the unease in lunchroom conversations. They wonder aloud if health care is really next and what to believe.

Group three is the hardest to accept. The people here revel in defending the indefensible. They are not so blind as to honestly miss the through-line of the Trump march toward authoritarianism. Instead, they make the opposite argument that they would make should the same policy be proposed by a Democrat because they can find some thread of reasoning on which to base the argument. They ignore the forest for a single tree. This is the neighbor I struggle most to understand. People here know the news. They know the cruelty, yet continue to defend. What payoff is there that is so valuable that they ignore the forest of evidence?

Given this landscape, how united can we ever be? Perhaps the answer lies not in nostalgia, but in a realistic view of how America has always worked: fractured, striving, and occasionally, surprisingly, resilient.

What Does a United America Look Like?

Over the past hundred years, Americans have disagreed, sometimes violently, about the role of government, our involvement in foreign wars like Vietnam and Afghanistan, and how far to federally assert the rights of misunderstood or oppressed groups. Today, we are disagreeing about the direction that the current Republican administration and its allies want to take the country.

Yes, this revolves around the all-powerful Executive concept. Yes, this includes the blurring and near-extinction of checks on Presidential power as Congress demurs. As serious and scary as these days are, they are not our first challenge.

In 1932, with the ravages of the Great Depression visible in every city and town, the country gave 57% of the vote to Franklin Delano Roosevelt. His popularity soared to hit 83% in 1942, an unapproachable level of support today.

In the height of the country’s division over Vietnam, Richard Nixon was elected President in 1968, garnering just 43.4% of the vote, due to the 3rd party candidacy of George Wallace, who captured five Southern states. Yet Nixon claimed the majority, even if it was mainly silent.

More recently, Trump was elected in 2016 with 46.1% of the vote. Biden received 51.2% in 2020, and Trump won again in ‘24 with 49.8% of the vote. To hear congressional Republicans tell it, that 49.8% represents an enormous mandate from the country. So what does a unified country look like in this era? We know that 49.8% of the vote isn’t it.

In Roosevelt’s time, united was more literal. In the lines for bread, Americans shared a common hope and belief that government could make things better. By the time we hit Vietnam, the sides were emotionally hardened and Thanksgiving could be a battleground. Yet, elections went largely unchallenged and the military stayed on the base.

This time, a larger number of us have taken a side and cling to that side for dear life. Still, there is a growing weariness in the land, the kind of civic fatigue that hums under the dinner conversation and through the inbox. More people are walking away from any form of national conversation. Left to ourselves, one by one, we may face a decision, not just about politics, but about what kind of neighbor, citizen, and person we choose to be.

Are We Ready to Decide?

Presidential historian Jon Meacham has said, ‘We’re a 51–49% country on a good day.’ It’s a reminder that waiting for overwhelming agreement is a fantasy we’ve never truly lived, even in FDR’s time.

But we’ve been united enough. Just enough. Enough to choose each other. Enough to believe that the idea of “American” was worth the trouble. Is it possible we could do that again? Not because it’s easy. Not because we suddenly agree. But because we just decided to.

That’s how it’s always happened. Not through miracles or mandates. Through choice. Through quiet, stubborn, daily decisions to stay in the room, to listen longer than is comfortable, to remember that the person across from you is still a citizen, still a neighbor, still a part of the story.

We won’t reunite because we’re forced to. We reunite because we choose to. Or maybe better said, because we finally say, “Enough!” to the constant partisan bickering, the nasty looks across the yard, the energy it takes to resist even the smallest act of neighborliness.

I’m not sure we can be saved without some soothing first. We’re tired, morally, emotionally, civically. We’ve been told to wake up, to rise up, to speak up. But few have asked how we’re sleeping, how we’re grieving, how we’re holding the weight of it all. What we want to hear isn’t always a distraction; sometimes it’s a lifeline. And if we’re honest, we need both: the balm and the call, the comfort and the conviction.

Am I saying that the country is on the verge of deciding to? No. There will be more pain. More anxiety. More clinging. But in my most optimistic moments, I am convinced that a day is coming. Maybe there will be a seminal event first. Or a moral leader arising. Or maybe, on some bright day across the land, more than half the people will wake up and just decide not to keep fighting everybody else, everyone different.

Yes, we’ve become divided. Cynical. Some of us stopped believing in the idea of “us.” There is no denying that anymore.

We can decide to show up anyway. To speak when it feels pointless. To listen when it seems unbearable. To remember that democracy isn’t a feeling, it’s a practice. And practices are messy.

We can’t wait for permission. So, we won’t. We can’t wait for perfect conditions. We just decide to change. Without ceremony, without consensus, we will decide to be a people again. Not a majority of us on one day, but faster than you might think. It won’t be this Thanksgiving. But maybe next. Or maybe on a day we don’t yet recognize as sacred.

That’s how it begins again. Not with certainty. Not with unanimity. But with a decision. A quiet, defiant, ordinary decision to belong to each other again. Even the Californians.

Bravo!